The Chamberlain Case – Installment 1 of 2

By Calvin Gnech, Criminal Lawyer and Legal Practice Director at Gnech and Associates

17 September 2020

The Death of Azaria

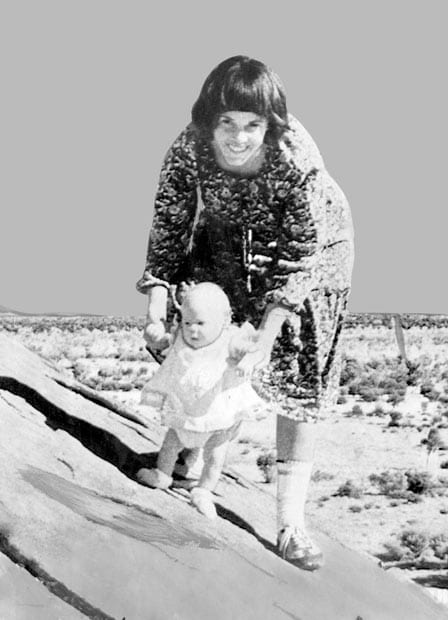

On 16 August 1980, Lindy and Michael Chamberlain, with their three children, Aiden (aged 6 years), Reagan (four years old) and Azaria (two months old) arrived in Ayers Rock for a family holiday. The following evening, life for the Chamberlain family would be changed forever.

In possibly the most talked about crime in modern Australian history, this case received worldwide publicity culminating in the 1988 movie, “A Cry in the Dark’, with Meryl Streep portraying Lindy Chamberlain.

This case involved three coronial inquests, the first commencing on December 15, 1980 and the last concluding on December 13, 1995. The original findings were broadcast live on television throughout Australia. The first inquest found that Azaria was taken and presumably killed by a wild dog (dingo). However, these findings were later quashed by the Northern Territory Supreme Court, and a second inquest ordered.

The second inquest found different and committed Lindy for the murder of Azaria and Michael for accessory after the fact, for trial.

The first day of trial was on 13 September 1982. Both Lindy and Michael were found guilty by the jury on October 29 1982. Lindy was sentenced to life with hard labour, and Michael ultimately received a suspended sentence.

They appealed to the Full Bench of the Federal Court but the appeal was rejected unanimously. Appeals to the High Court were also unsuccessful with the court handing down a decision three to two upholding the convictions.

The Evidence as Summarised by the High Court

The Evening of the 17th

At about eight o’clock on the evening of 17 August Mr and Mrs Chamberlain, Aiden and Azaria were at the barbecue for the purpose of having their evening meal. Mrs Chamberlain was nursing Azaria and seemed happy and cheerful. Reagan was in the tent, in bed and apparently asleep. Two other campers, Mr and Mrs Lowe, were also at the barbecue area, and both saw Azaria; at the trial it was common ground that the baby was then alive. Mrs Chamberlain, carrying Azaria and followed by Aiden, left the barbecue area and walked in the direction of the tent, intending to put both children to bed.

Her evidence as to what then occurred was as follows. She placed the baby, who was asleep, in a bassinet in the tent and tucked her under the blankets. Aiden said that he was still hungery, so she went to the car and got a tin of baked beans, went back to the tent and then, with Aiden, returned to the barbecue area.

There is no doubt that she did return to the barbecue area, accompanied by Aiden and carrying the tin of beans and a tin opener, about five or ten minutes after she had left. She seemed normal and quite composed. No one saw any blood on her clothes or on her person.

The Crown Case

The Crown case is that during this short absence from the barbecue area, Mrs Chamberlain took Azaria into the car, sat in the front passenger seat and cut the baby’s throat. According to the Crown, the baby’s dead body was probably left in the car (possibly in a camera bag) and was later that evening buried in the vicinity by Mr and Mrs Chamberlain.

Soon after Mrs Chamberlain had returned to the barbecue area she again commenced to walk in the direction of the tent. According to the case for the defence, and according to some of the witnesses for the prosecution, she did so because Mr Chamberlain had heard the cry of a baby from the tent.

If the cry was that of Azaria, it is obvious that the Crown case cannot succeed. It is convenient to state first the account given in evidence by Mrs Lowe, who had met the Chamberlains only that night, had no association of any kind with them, and obviously had no motive to tell anything but the truth, although her evidence of course could have been mistaken.

Mrs Lowe’s Evidence

Mrs Lowe was asked what happened after Mrs Chamberlain had returned to the barbecue with the can of beans, and gave this evidence:

“Well she was just standing there. I heard the baby cry, quite a serious cry but not being my child I didn’t sort of say anything. Aidan said: ‘I think that’s bubbie crying’, or something similar. Mike (Mr Chamberlain) said to Lindy (Mrs Chamberlain): ‘Yes, that was the baby, you better go and check.’ Lindy went immediately to check. I saw her walk along the same footpath that they’d been on. What happened next? . . . She was in the area on that footpath closest to where the car and tent was, only inside the railings, and yelled out the cry: ‘That dog’s got the baby.’”

Mrs Lowe said that the cry which she first heard definitely came from the tent; and that she was positive that it was the cry of a small baby and not of a child. The cry was loud and sharp but seemed to stop suddenly. Mr Lowe did not hear the baby’s cry; he said that he was heavily engaged in conversation. He said that Mr Chamberlain said to his wife: “Was that the baby?”, that Mrs Chamberlain went to check and that when she was about 5 yards away she cried out: “That dog’s got my baby.”

Another camper, Mrs West, was at the time in her tent which was near to that of the Chamberlains’. She heard from the direction of the Chamberlains’ tent the growl of a dog and then, fairly soon afterwards (or, as she also said, five or ten minutes later, she heard Mrs Chamberlain cry out: “My God. My God. A dingo has got my baby.” Her husband, Mr West, also heard the growl of a dog. (at p541)

Blood in the Tent

A number of witnesses saw blood in the tent, although no one seems to have made a very thorough inspection of the tent or its contents that night. Most of the witnesses who looked into the tent described what they saw as spots or sprays of blood on blankets and other articles in the tent. Mrs Lowe said that she saw “a dark red wet pool of blood”, about six inches by four inches in size; no one else saw such a pool.

The Tracksuit Pants

A pair of tracksuit pants, belonging to Mrs Chamberlain, were subsequently sent by her for dry cleaning at Mount Isa. There were marks on the pants which resembled blood stains and which responded to the appropriate cleaning agent for blood. The marks were on the front and below the knee; the stains, or spots, appeared to be splattered or flicked on, and tapered off in size towards the bottom of the pants. The Crown case was that Mrs Chamberlain must have been wearing the pants when she committed the murder.

The evidence is clear that she was not wearing the pants either when she left the barbecue area carrying the baby or when she returned to it after she had obtained the tin of baked beans. If she killed the baby and was wearing the pants at the time of the murder, she must have donned them in the tent and taken them off again before she returned to the barbecue. She said that she did put the pants on about three-quarters of an hour or an hour after the baby had disappeared, because it was cold, and that she had thereafter worn them for a considerable time.

The Track Shoes

The track shoes which she was wearing may have had some blood on them but it was not proved that any other article of clothing that she wore that night was blood-stained.

In September 1980 she handed the track shoes to the police at Mount Isa and said that they had had blood on them but had since been washed and the tests for blood proved negative. Her explanation for the presence of blood was that it must have got on the shoes when she crawled inside the tent.

Other Evidence

There was other relevant evidence that was considered such as the untruthful statements of both Lindy and Michael to authorities. Of significance to the Crown was that in September 1981, police finally seized the family vehicle and took swabs from various locations within the vehicle. Blood was located and there was a large body of expert evidence at trial as to the blood belonging to Azaria or not.

For the purpose of this article if we overlook the detail of this expert evidence, it was ultimately found that the jury were not entitled to find beyond reasonable doubt that the areas of blood in the front section of the car contained foetal haemoglobin (baby blood). However they were entitled to have regard to those areas of blood as showing first that there was blood in the car which could have been Azaria’s blood, and secondly, that the blood was unlikely to have been deposited where it was found by any other person who had bled in the car.

Circumstantial evidence

This case is often referred to as an authority for dealing with circumstantial evidence. That is the case but there are also a number of other cases that are similar in nature such as: Shepherd (1990) 170 CLR 573, 578 and Perera [1986] 1 Qd R 211.

The Queensland Supreme and District Court Benchbook describes circumstantial evidences as:

Circumstantial evidence is evidence of circumstances which can be relied upon not as proving a fact directly but instead as pointing to its existence. It differs from direct evidence, which tends to prove a fact directly: typically, when the witness testifies about something which that witness personally saw, or heard. Both direct and circumstantial evidence are to be considered.

To bring in a verdict of guilty based entirely or substantially upon circumstantial evidence, it is necessary that guilt should not only be a rational inference but also that it should be the only rational inference that could be drawn from the circumstances. If there is any reasonable possibility consistent with innocence, it is your duty to find the defendant not guilty. This follows from the requirement that guilt must be established beyond reasonable doubt.

Considering circumstantial evidence

When considering circumstantial evidence the question often arises whether the proper method of approach to the facts is for the jury to consider each item of evidence separately, and to eliminate it from consideration unless satisfied about it beyond reasonable doubt.

The High Court referred to Reg v Beble (1979) QD R 278:

“It is not the law that a jury should examine separately each item of evidence adduced by the prosecution, apply the onus of proof beyond reasonable doubt as to that evidence and reject if they are not so satisfied.”

At the end of the trial the jury must consider all the evidence, and in doing so they may find that one piece of evidence resolves their doubts as to another. For example, the jury, considering the evidence of one witness by itself, may doubt whether it is truthful, but other evidence may provide corroboration, and when the jury considers the evidence as a whole they may decide that the witness should be believed.

Ultimately a circumstantial case must be assessed as a whole, and not piecemeal all of the evidence (R v Shepherd). In R v Aboud [2003] QCA 499 the jury was correctly told to treat evidence about the origin of phone calls to a murder victim as merely one element in a ‘circumstantial matrix’.

Conclusion

In 1985, the Northern Territory rejected an application by the Chamberlain Innocence Committee for a full judicial inquiry into the case, and also rejected an application by Lindy for early release.

On February 2 1986 a matinee jacket matching the description of Azaria’s jacket worn on the day she went missing, was discovered at Ayers Rock in an area full of dingo lairs. Five days later Lindy was released from prison and the Northern Territory Government announced a new inquiry into Azaria’s death. The Inquiry, commissioned before Justice Trevor Morling, found evidence against the Chamberlains was not substantial.

A Special Act

Amazingly, in 1987 a special Act was passed by the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly to permit the Chamberlains to apply to the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory to have their convictions quashed. On 15 September 1988, Lindy and Michael Chamberlain returned to the Darwin Courthouse where they had been convicted six years earlier.

Convictions Quashed

The three judges of the Court of Criminal Appeal took less than two minutes to announce their unanimous decision to quash the Chamberlains’ convictions. The finding being that “the convictions having been wiped away, the law of the land holds the Chamberlains to be innocent.”

In 1992, Lindy was awarded $1.3 million in compensation from the government for wrongful imprisonment. On December 13, 1995, a third coronial Inquest found “Azaria’s death cannot be determined” and the case remains unsolved.

More to the Story – Frank Cole

We all thought this saga had finished, that was until 2004 when Frank Cole took a lie detector test to prove his story that in August 1980, he shot the dingo that killed Azaria and showed her body to his companions. Cole kept the story secret, in a pact with his mates, for 24 years for fear of prosecution.

Part 2 – Installment 2 will be posted next week.